Trading Articles

Bond Markets And FX Effects By Tyler Yell

The actions of the central banks have significant effects on the financial markets. In this article, we look at the bond markets to see how they can impact the forex markets. In an annual letter to shareholders, JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon said the bond market and the volatility that is likely to come is a core concern and would have major impacts in forex. The sharp spike in prices and subsequent drop in yields on October 15, 2014 confirmed his fears and should keep you on high alert of this nearly $93 trillion market. This article will unpack Dimon’s statement and walk you through an overview of the state of the bond market, the effects of quantitative easing (QE) on the bond market, and how bonds affect trading capital flows and therefore forex prices. In addition, I’ll look at common occurrences between QE, bond prices & yields, capital flow, and opportunities from resulting forex moves.

Price Vs Yield

For those unfamiliar with bond market pricing, there are two key concepts to understand. First, you should note that price moves inversely to yield (Figure 1). When the yield is moving lower, price is rising. Price goes higher when buyers—who are currently the central bank and risk-averse institutions—buy new issues.

The global benchmark maturity in government debt is the 10-year note, which tells us how much or how little a government has to pay to borrow money from the market over the next 10 years. The economies that we’ll be looking at and their subsequent bonds are the US 10-year Treasury note, Japanese government 10-year bond, and the German 10-year bund.

A Market Interrupted

Each country’s 10-year yield has dropped precipitously over the past 30 years. While reversals are rare—and many think it must happen since several long-term government debt products are coming close to zero yield—if it were to happen, the effects will be remarkable (Figure 2). One of the first places you will see the effect is in the forex (FX) market, and fund managers expect this to bring once-in-a-generation FX opportunities.

One of the first places you will see the effect is in the FX market, and fund managers expect this to bring once-in-a-generation FX opportunities.

When central banks like the Federal Reserve System in 2008 or the Bank of Japan in late 2012 engaged in QE, two distinct patterns emerged. The first pattern was that prosperity and growth were promised upon the purchasing of bonds by the central bank. The promised prosperity was to come by lowered borrowing costs, which should have driven down rates and encouraged people to borrow and thus build the economy back up. But that took a while in some places and hasn’t happened in others.

The second and less desirable pattern was a flow of capital out of the economy once a central bank started intervening in the debt market. This outflow was a market reaction to an unwanted force of central bank intervention by way of aggressive bond buying in order to ensure liquidity while at the same time, bringing down yields and therefore, borrowing rates. In a world of unintended consequences, this was done with good intentions but caused the people at the helm of the largest markets to stand back, reducing overall market participation from traditional liquidity providing traders.

Suggested Books and Courses About Investment

The $25 trillion dollar government bond market has a large problem on its hands that won’t be easy to solve. Simply put, the bond market has ceased being much of a market with two-way participation. This is a problem because when the Federal Reserve or central bank, which is participating in QE, decides that it is time to unwind its portfolio, they are going to have to find a party willing to buy government-manipulated low-yielding debt. As you will see down the road of this article, self-interested parties will likely not be interested, which means we’ll have a liquidity crisis such as the one Jamie Dimon feared, causing sharp volatility and harmful moves.

Capital Flow

The global foreign exchange market is directed by capital flow. Trade and capital flow are the reason for the rising and falling of an economy and subsequently, the value of a currency. When a central bank begins QE by purchasing government debt in order to stimulate the economy, money has a habit of leaving for the reasons I mentioned earlier, while money that was already in the system is now buying up debt. While the bonds are moving higher in price and the yields are moving lower, the net capital flow is definitively one directional after the engagement of QE.

The dependable pattern emerged once again. Money left aggressively as the central bank, or the bond market bully, showed up to the market’s playground. Once again, little new money or capital flow and trade flow was coming into the eurozone and the capital used to purchase government debt, which was anything yielding above the deposit rate, set an artificially low -0.2%.

Not until there is a light at the end of the tunnel for an end of central bank activity will money begin to flow into the economy. A depressing and telling trend is how many famous value investors have altogether stopped investing in many markets because the central bank activity has fueled unreliable valuations similar to the panic top in technology companies in 1999.

What’s To Come?

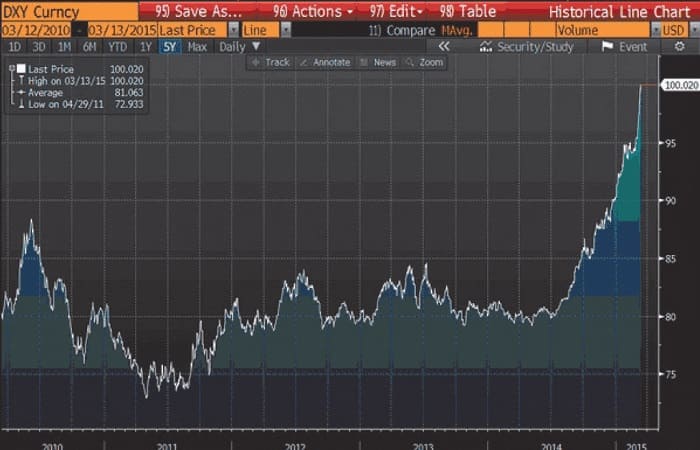

The other side of the pattern is that when central banks begin discussing the terminus of QE and the eventual rising of interest rates, which is associated with normalization of market activity, the currency strengthens. The US dollar had an effect similar to a beach ball that was held underwater finally being let go and racing skyward. From summer 2014 to March 2015, the dollar had a bottle rocket effect, leaving every other currency in its dust (Figure 3). The dollar was the only currency the central bank was discussing when it came to raising reference interest rates within the year.

The effect of this normalization is that capital comes rushing back for investment opportunities. That is why markets are so resilient. What is at one time a mindless sell soon becomes a mindless buy. When that happens, capital could and likely will flow into the eurozone similar to how it was in the United States over the last year and if history is any indication of what could happen in the future, investors and position-based traders will be scratching their heads as to why they did not buy the euro when they had the chance to at such depressed levels.

As institutional investors and capitalists have a habit of doing, opportunities are being sought out on the other side of QE from the European Central Bank. The famed bond trader Bill Gross recently stated that the German 10-year bund would be the short of a lifetime rivaling even the gravity-defying drop in the British pound in 1993, where well-known investor George Soros netted a profit of over €1 billion.

The First Big Shoe To Drop?

I have focused mostly on government debt and rightly so because there are clear patterns that suggest there is another market that should hold your focus. The high-yield — or “junk” — bond market attracted most of the money that left government debt after central bankers seized market supply. Yield seeking money quickly found high-yield debt as a favorable option. Naturally, when the market senses demand, supply soon follows, but this could be a problem.

High-yield or “junk” is not just a clever name. It gets its name from the increased likelihood of default by the issuer. Building on the prior argument that central bank action has driven down reference rate yields, you need to be aware that any type of global normalization will increase rates. As a result, you’ll likely see a wave of defaults from high-yield debt issuers, causing a shock to a secondary debt market.

Defaults would arise because ineffective and inefficient companies that are supposed to fail in a normal economy were not failing in our low-interest environment. That’s because they’re being supported by cheap money, and thus, the rising and falling tide that normally lifts or drops all boats was replaced by an artificial tide that will soon leave the picture. When that happens, some boats that should have fallen to the seafloor years ago are up for sale at premium prices, which is appropriately scaring away capital.

The secondary debt market currently seems to be humming along fine for now. However, if a global recovery develops in a way that causes investors to sell off government debt, a reaction would be that rates and subsequent borrowing costs would aggressively rise. An aggressive rise in borrowing costs would mean that a global recovery that caused government debt to sell off in plight for better higher yielding assets would destabilize a major market. The secondary debt market is already borrowing at relatively high costs and if the base line increases for borrowing, as it currently sits at historic lows, then a great number of companies with current thin margins would likely not exist when borrowing costs normalize, whatever that means going forward. This may be a good time to remember what 20th-century economist Hyman Minsky stated: “Stability begets instability.”

In Closing

The bond market has become the playground of central banks engaging in QE. This has caused normal market participants to run away to other economies that are not engaging in QE or are finishing up QE and are looking at raising rates. This causes volatility in the currency market as an effect. The volatility often means a sharp drop in the currency of countries engaging in QE and a strong rise in countries looking at normalizing monetary policy. As trillions of dollars in central bank portfolios look to be unwound over the following years, currency market volatility looks to be the new norm and no longer the exception.

Tyler Yell, CMT, is a currency analyst and trading instructor for DailyFX.com, a forex market news and analysis site.