Trading Articles

Winning The Battle Of The Grains By Jay Kaeppel

Is there a way to exploit the seasonal tendencies of these two markets? No, this contest is not going to involve any kind of a taste test. Nor will this competition offer the wit and humor of Mad magazine’s “Spy vs. Spy” serial cartoon. Still, to traders looking for a tempting trading idea to snack on, the interplay between corn and wheat can be, well, quite tasty. As everyone knows, corn and wheat are both essential grains that are planted, grown, and harvested and then used to create myriad food products. While corn can be eaten whole or milled, wheat typically is milled in order to make it useful for creating other food products.

But there is another key difference between these two grains, and that is the time frame in which they are primarily grown. While both grains are grown in various locations around the globe, in the United States the bulk of the corn and wheat is grown in the Midwest. Given the vagaries of weather in that region, there is the potential for great uncertainty from year to year regarding the size of a given year’s crop for either or both of these grains. But the real key to playing the game of corn versus wheat is in understanding the difference between the planting cycles of these two grains and the psychology of supply concerns.

A TIME TO REAP, A TIME TO SOW

The greatest period of doubt for a given grain is during that time when no seeds are in the ground. At that point, no conclusions can be drawn about the size of the next impending crop. As a result, that is when a given grain is most likely — although by no means certain — to rise in price. Likewise, once the growing season is reaching its end, the outcome of the impending harvest is pretty well known, for better or for worse, and prices will tend to lose any “fear” premium that might have been built in earlier in the growing cycle. As it turns out, corn and wheat have very different growing seasons, so in theory the price should rise and fall at different times. And as it turns out, this tends to be the reality.

In the US Midwest, corn is planted in the spring, grows during the summer, and is harvested in the autumn. Wheat, on the other hand, is planted between mid-August and October and harvested from mid-May to mid-July of the following year. As a result of these different planting seasons, the corn crop is in greatest doubt during late winter to early spring, while the wheat crop is most in doubt between midsummer and early autumn. The price of any commodity is more likely to rise when there are doubts or concerns about supply. Conversely, the price of any commodity is more likely to decline when the supply appears to be abundant.

So the obvious question from a trading standpoint: Is there a way to exploit the seasonal tendencies of these two markets? As you will soon see — with the caveat that no method is ever perfect — the answer appears to be “yes.”

FOR ALL THINGS A SEASON: PART I

Let’s look at a time period during which we might expect corn to outperform wheat. The time frame begins at the close of the fifth trading day of February each year and ends at the close of trading on the sixth trading day of April each year. We will assume that at the close of trading on the fifth trading day of February, the following trade is made:

- Sell short 10 May wheat futures contract

- Buy a roughly equal dollar amount of May corn futures contracts

This requires some explanation and some calculations. Both corn and wheat futures contracts are actively traded at the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT). For both contracts, a one-cent move in the price of the underlying contract is worth $50. So if corn advances $0.05 in price, the value of the contract increases by $250 ($50 * 5). Likewise, if wheat declines $0.10 in price, the value of that contract declines by $500 ($50 * 10).

So let’s assume that near the close of trading on the fifth day of February, May wheat futures are trading at $4.88 a bushel. Since each cent is worth $50 and there are 488 cents, the value of one futures contract is $24,400. For our example we assume that we always trade a 10-lot position of wheat. Therefore, we sell short 10 May wheat futures contracts and the total contract value of these 10 contracts is $244,000.

Suggested Books and Courses About Commodity and Futures

Now let’s assume that at the same time the May corn futures contract is trading at $3.6525 a bushel. At $50 per penny, the value of one futures contract is $18,262.50. If we divide the value of 10 wheat contacts ($244,000) by the value of one corn contract ($18,262.50), we get a value of $13.36. This indicates that we should buy 13 corn contracts (since we cannot trade fractions of contracts). The dollar value of the corn contracts purchased is $237,413, which is as close as we can get to the value of the wheat contract sold short.

As I write this, the margin requirement to trade one corn contract is $1,688 and the margin requirement to trade one wheat contract is $1,620. So in theory a trader who wanted to buy 13 corn contracts and sell 10 wheat contracts would have to put up $38,144 in margin (13 * $1,688 + 10 * $1,620). However, most brokerage firms recognize the reduced risk associated with trading certain spreads and offer greatly reduced “spread margins.” According to Dan O’Neil of optionsXpress, the spread margin for this trade is only $14,985. This amount will vary as time goes by based on the price level and volatility of fluctuations in the underlying futures contracts. Still, the primary point is to recognize that a large position can be established at a relatively low level of margin (a little over 3% of the total contract value in this example).

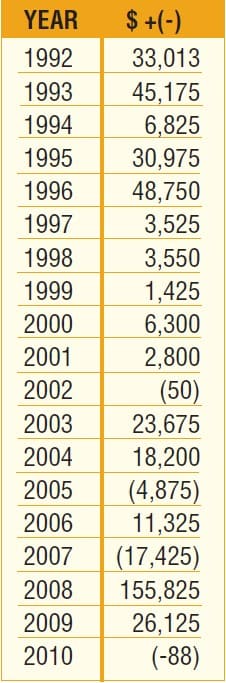

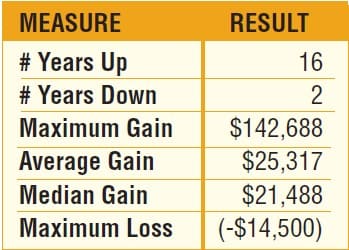

According to O’Neil, “Spread margins allow traders to take advantage of opportunities where some of the risk is offset by allowing them to commit a smaller amount of trading capital, thereby increasing their leverage and potential rate of return.” Figures 1 and 2 display the results of making this trade each year since 1992. The results shown in Figures 1 and 3 make the following assumptions:

- At the close of trading on the fifth trading day of February, 10 May wheat futures contracts were sold short and a roughly equivalent dollar amount of corn futures contracts were purchased.

- No adjustments were included for slippage and commissions.

- No stop-loss or profit target provisions were employed, and thus, intratrade results may have witnessed much larger open gains or losses during the course of the trade.

Now let’s look at another time frame that favors wheat prices.

FOR ALL THINGS A SEASON: PART II

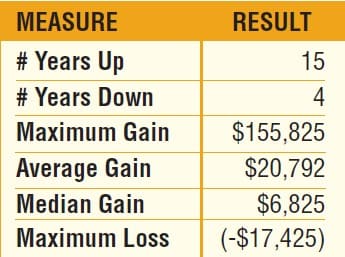

Now let’s look at a time period when we might expect wheat to outperform corn. The time frame in consideration begins at the close of the 14th trading day of June and ends at the close of the 17th trading day of October. We will assume that at the close of trading on the 14th trading day of June, the following trading is made:

- Buy 10 December wheat futures contract

- Sell short a roughly equal dollar amount of December corn futures contracts

Once again we must calculate the approximate dollar value of 10 wheat contracts and then equate that into a roughly equivalent dollar amount of corn futures contracts. So let’s say that December wheat is trading at $6.1575 a bushel. The dollar value of a 10-lot long position is $307,875 (615.75 * $50 * 10 contracts).

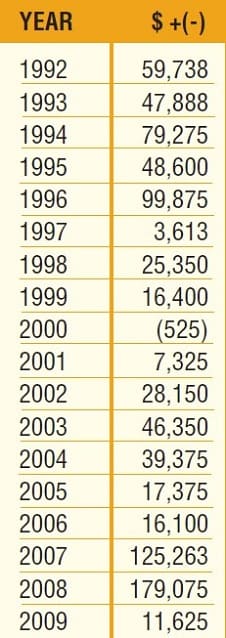

Assume that at the same time December corn futures are trading at $4.2375 a bushel. This works out to $21,187.50 per contract. So if we divide the value of our 10-lot wheat position ($307,875) by this value we get 14.53. In this case, we will round up and sell short 15 December corn contracts, or a total dollar value of $317,812.50. Figures 3 and 4 display the results of making this trade each year since 1992.

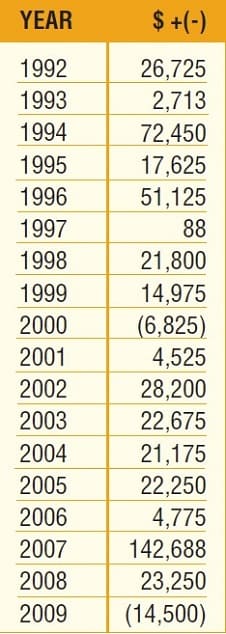

COMBINED RESULTS

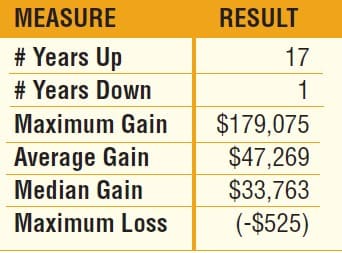

Figures 5 and 6 display the annual results using the methods described previously for trading corn and wheat futures. On the face of it, the results are fairly impressive in terms of net results. There are, however, several important caveats to keep in mind. First off, trading a 10-lot of wheat futures and a roughly equal dollar amount of corn futures — even when using more favorable spread margins — entails a meaningful financial commitment and a significant degree of risk. Second, remember that all of the results shown in this article assume no profit targets but no stop-loss orders as well.

Therefore, while the largest losing trading shown from open to close was -$17,425, the intratrade loss for any single trade could have been greater. As a practical trading matter, a trader should have some sort of stop-loss provision in place for each and every trade. And if a stop-loss is triggered, a trader could miss out on a subsequent price move in the anticipated direction.

SUMMARY

Opportunities are everywhere in the financial markets. Sometimes, uncovering and implementing them involves doing some digging and/or acting on a leap of faith. The methods described herein are a case in point. Once a person understands the basics of how and when grains are planted and harvested — and how prices typically react during different phases of the growing cycle — it makes sense that certain spreads such as those discussed here can work with a high degree of consistency. Nevertheless, no one should jump blindly into any trading strategy without analyzing it to determine if we have the financial and emotional wherewithal to take advantage of the opportunity at hand.

Jay Kaeppel, an independent trader, is the author of Seasonal Stock Market Trends and writes a weekly column titled “Kaeppel’s Corner” for Optionetics.com. He may be reached at the discussion boards at Optionetics.com.