Articles

The Cycles of Wall Street By Edward R. Dewey

Many scientists are presently involved with cycles, and the number is growing each year. But for the most part each is studying cycles in his own particular field-economic cycles, earthquake cycles, cycles of disease, cycles of animal abundance, and many more. Few scholars, if any, outside of the Foundation for the Study of Cycles are studying cycles as such. One reason for this state of affairs is that among those who have not examined the evidence there is a certain amount of skepticism about the meaningfulness of these cyclic behaviors.

To allay this skepticism I thought it would be helpful if our method and results were to be certified, as it were, by some cf the world’s leading statisticians. This has been done, and I still think it was a good idea, although the concept was somewhat naive on my part. I believed that scientists would come flocking to the study of cycles once they were presented with irrefutable statistical proof that we were dealing with facts.

In the past few years two friends have argued that my idea was wrong. And what makes their comments particularly interesting is that they are the last persons in the world from whom one would expect advice of this sort. They are, of all things, statisticians themselves, and among the country’s best, I might add. They maintain that a fact without a theory to explain it, especially if it doesn’t fit into the ordinary concepts of how things “ought” to behave, is merely a disturbing something to be ignored and, if possible, forgotten. Independently both these men said, in effect, the same thing:

“You have already made enough discoveries to convince any reasonable person that these mysterious behaviors do exist. It would be nice, of course, to prove by mathematics the soundness of all that you have done but don’t let that be your prime concern. You are already at the place where you can say, ‘These things are so.’ Now go on from there and find out why!”

I do not mean to imply that my friends discount or decry statistical proof. They mean that all the statistical proof in the world, by itself, without some sort of theory or explanation, will not create the stir necessary to initiate full scientific participation in the study of cycles. A mere fact, by itself, makes no impact on the scientific community, especially if it runs counter to accepted ways of thinking. Were he alive and reading these words, Galileo would be nodding his head sadly. All of this returns us to our search for the cause of our mystery.

Actually, however, we don’t need to know cause to put a knowledge of cycles to practical use, as you have seen. We now have good and easy methods of detecting, isolating, evaluating, and projecting cycles. We must, however, remember that cycles are not the whole answer. Cycles are distorted by randoms. Moreover, the cycles themselves occasionally “black out,” miss a beat, give us two waves where there should be three, or evidence some other aberration before they get back on the track. Cycles, as yet, are not absolutely dependable, but they certainly help us to know the probabilities. And nowhere is this more evident than in the stock market.

Suggested Books and Courses About Market Cycles

Not even the most ardent “cyclomaniac” would claim that all stock-market fluctuations are the result of cyclic forces. Even if we knew all there was to know about cycles in the stock market, the most we could do would be to predict that part of the market behavior that was caused by cyclic forces.

But we can report facts that you should take into account if you are an investor, facts that you are not likely to learn from the hundreds of excellent books on the subject of stocks and bonds. I have, in my library, a volume that is generally acclaimed as the “investment bible” for anyone involved with the buying and selling of securities. I have no doubt that at least one copy can be found in nearly every investment broker’s office in the country.

Now here in its 700 pages of theory and practice is there a single mention of cycles per se! And yet, perverse, frustrating, unexplainable though cycles may be, you cannot ignore the fact that they exist if you are ever going to approximate the future probable behavior of the stock market. Before his death General Dawes, mentioned briefly in the last chapter, asked me to inaugurate a service for banks and businessmen that would tell them what to expect regarding future activities of our economy. He suggested that I should charge a fair price for the service, that he would subscribe, that his bank would subscribe, and that he personally would write letters to all banks in the Midwest urging them to subscribe too. Naturally, I was pleased and flattered by his tempting offer.

However, I turned it down for the very simple reason that I did not feel I knew enough about cycles to be able to accept the money. Over two decades have passed since General Dawes made his proposal. If he were alive and were to make that same proposal today, I would still decline his offer, for despite all the clues we have uncovered in the past twenty years, our ignorance still outweighs our knowledge. We have countless pieces that obviously belong to our “mosaic.”

They are real. But no one, yet, has been able to put them all together. No one, yet, has solved the great cycle mystery. Perhaps this is the reason why the subject of cycles in the stock market is so carefully avoided in most investment literature. It cannot be substantiated scientifically, it cannot be catalogued, it cannot be categorized, and it does not complement any familiar investment theory. If it doesn’t fit in anywhere, they say, let’s leave it out, for it would only further complicate an already complicated subject. And furthermore, if cycles really do exist, why is there no scientific explanation for their cause? Thus goes their reasoning.

How sad.

The Complicated Beat

Stock prices, like most other phenomena, fluctuate in cycles. More exactly, like our complex cycle of rainfall in the previous chapter, stock prices act as if they were influenced by a number of different cyclic forces, all acting at the same time. Let me give you two more examples of this type of behavior.

The cardiograph record of your hearbeats shows a simple rhythm of perhaps seventy-eight beats a minute. But imagine what that chart would look like if you had a second heart that beat, let us say, forty-one times a minute. Now suppose you had three hearts, one beating seventy-eight times a minute, the second fortyone times a minute, and the third twenty-two times a minute. Can you imagine how erratic the chart of your heartbeats would be?

And, of course, if you had ten or twenty or thirty hearts, each beating at its own special rate, you would have a mixture of ups and downs that would be impossible to unscramble unless you knew something about cycle analysis. Or suppose we had a dozen or more moons, all of different masses and all revolving around the earth at different rates. Can you visualize how complicated our tides would be? Of course, knowing the laws of physics, we could work from cause to effect, and knowing the cycles of each of the moons by observation, we could trace their effect on the oceans.

But suppose our sky was perpetually overcast, like the sky of Venus, and we did not know the moons were there. It would be a long time, I am afraid, before it would occur to anyone that the seemingly haphazard movement of the water was due to anything but the winds. Patient work over many years might be necessary before the mystery could be unscrambled, the various moons postulated with certainty, and predictions made with accuracy.

Conditions similar to these prevail in the behavior of stock market prices. We know that there are cycles there, but they are fully as complicated as our pulse would be if we had a multitude of hearts, or as the tides would be with a multitude of moons.

Consequently, I have lived for many years in a dilemma that is still unresolved. On the one hand, I have been reluctant to report about any one cycle in the stock market, just as a student of the tides in a world with many moons would hesitate to tell you about any one cycle in the levels of the waters. On the other hand, I still do not know enough to tell you about all the cycles. I knew even less in 1944 when I prepared a stock-market forecast that received considerable attention.

Early in 1944, at the urging of a large brokerage firm in New York City, I prepared and delivered to them a forecast of stock market behavior. To complete this forecast I made a reconnaissance survey of possible medium- and long-term cycles in the stock market. The data used were annual averages of the Clement Burgess Index 1854-1870 spliced to the Combined Index of the Standard and Poor’s Corporation Index 1871-1943.

Only ten cycles over 4 ½ years in length were used in my projection, ranging from one of 4.89 years to one of twenty-one years. The forecast was as crude as Edison’s first incandescent light. It employed only annual figures instead of daily, weekly, or monthly figures, which would have provided greater accuracy. No cycles less than 4 ½ years in length were included, although there are, without question, shorter cycles whose influence might have advanced or retarded the crests from the time indicated by the longer cycles. Also, since these stock figures go back only to 1854, those cycles of ten years or longer have had an opportunity to repeat only nine or less times, making their exact length difficult to pinpoint.

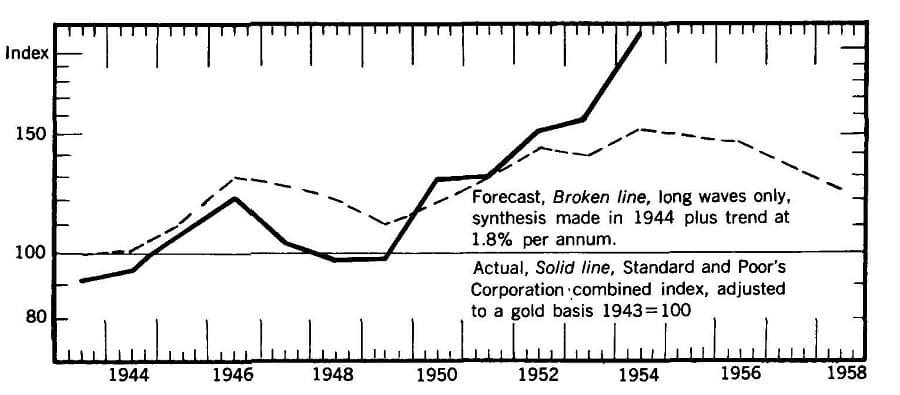

Anyway, this fool .rushed in where men of good sense feared to tread, and the ten-year results can be seen in Figure 33. The ten cycles are synthesized into one forecast curve (broken line); the solid line shows what actually happened. The “forecast” correctly called for 1946 as the end of the bull market, correctly called for 1949 as the end of the bear market, and called for 1954 as the end of the bull market that followed. Over a ten-year period it had a gain-loss ratio of 185 to 1.

Fig. 33. A Stock-Market Forecast

This forecast was prepared early in 1944 using figures through 1943 only. For the ten years during which the market behaved as predicted, the gain-loss ratio was 185 to 1.

From the moment of its introduction everyone who came into contact with the forecast was warned by me that it was not to be considered as a forecast but merely as the result of a reconnaissance survey that had to be surrounded by the word if. It was merely a mock-up to indicate possible future behavior if the indicated cycles were real and continued, if the length, shape, amplitude, and timing of the cycles had been correctly determined, if there were no other long-term waves that had not been taken into account, if the short-term waves less than 4 ½ years in length (which were not used) did not gang up on the long-term waves and distort them, and if no accidental factors entered into the situation.

After ten years the “forecast” went awry, but it is still a source of wonderment and pride to me that it continued to function accurately for a decade despite its primitive preparation. After all, Edison’s first filament glowed only for a few hours.

Like the first light bulb, we have come a long way in our study of cycles since our first minor successes. The use of computers has greatly accelerated our progress at the Foundation during the past few years, but they have also shown the immense amount of work still ahead before we can forecast stock-market activity successfully. In 1965, for example, an analysis of stock prices was undertaken with computers, searching for all possible hints of cycles in common stocks from 1837 up to that time.

When the search was completed and the computers had ceased to purr and the final logarithm table had been put away, we had discovered hints of thirty-seven possible cycles in stock-market prices, ranging in length from 21 ½ years to nearly 111 years! Even the possibility of ten or twenty moons affecting our tides or ten or twenty hearts beating complex rhythms on our cardiograph chart seems fairly simple in comparison. To refine and verify all these cycles will take years. Eventually it will be accomplished, but while you are waiting, let me tell you some of th~ facts we already know about stock-market behavior and forecasting.